NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE

November 26, 2006

Playing With Ideas

By DAPHNE MERKIN

I am sitting almost next to Sir Tom Stoppard in the dark. As befits a man who is not overly fond of too much proximity (he has been quoted as saying that he wants any biography of him to be “as inaccurate as possible”), he has left a seat between us. The two of us are camped in an otherwise empty row in a sea of unoccupied rows at the back of Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater on a Sunday afternoon in early October, observing the world of the passionately sparring but frequently lovelorn 19th-century Russian intelligentsia conjured by Stoppard’s high-jumping imagination in “Voyage,” the first part of his vaultingly ambitious eight-hour trilogy, “The Coast of Utopia.”

“The Coast of Utopia” made its debut in London in August 2002, under the direction of Trevor Nunn, and received decidedly mixed reviews. One critic for The Independent noted that “the trilogy is, throughout, intelligent, lucid and eloquent and enlivened by the author’s wit and eye for the absurd” but also saw fit to observe that the plays “are like an overinclusive crash survey of the period, a theatrical supplement to one of Stoppard’s prose sources.” In New York, the three parts (the other two are “Shipwreck” and “Salvage”) will be rolled out one by one, with audiences able to see the individual plays in succession as well as in three one-day marathon performances on consecutive Saturdays at the end of the run; London’s National Theater rehearsed and opened the three plays at the same time. When Jack O’Brien, the American director of “Utopia” (he also directed Stoppard’s “Invention of Love” and “Hapgood” at Lincoln Center Theater), first saw the London production with Bob Crowley, one of the two set designers on “Utopia,” they were “poleaxed” by the end of the night. “I hadn’t seen its like before,” O’Brien said. “I thought I was watching something possibly new lurch to its feet and then stumble across the stage.” He also thought the play was too long and passed his concerns on to Stoppard. “I told him it needed to be thinned out. He seemed baffled, sweetly baffled.” Now, four years, five or six scripts, a barrage of cuts and an entire directorial re-envisioning later, the Lincoln Center production of “Voyage” is finally ready for the curtain to open on Monday night.

Stoppard and I are watching what is known in the business as a tech rehearsal. Scattered in the theater around us are about 20 people, all involved in making sure that “Voyage,” which flits around in time and place at a sometimes hectic rate, proceeds without a discernible hitch. Some of them are fairly young; they sit in clusters of two or three in front of computer screens that emit a soft light, like glowworms, while others stand or straddle high stools, wearing earphones as they keep a close eye on video monitors. When I ask Stoppard what his role is during this phase, he answers in his characteristic self-mocking style: “Every two and a half hours I contribute a tiny thing.”

As is customary during the initial weeks of rehearsals, the cast is mostly wearing street clothes; Ethan Hawke, who plays the charming but self-centered anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, is in a T-shirt and jeans, while Billy Crudup, who plays the diffident yet intellectually confident literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, sports, in what appears to be a gesture toward sartorial verisimilitude, a loose white shirt that is gathered around the neck and puts me in mind of a Slavic folk dancer. As the actors go through their paces, O’Brien and his team of set, sound and lighting designers focus on smoothing out any creaks and lags in the production.

“The Coast of Utopia” spans a period of 35 years — it begins in 1833, at Premukhino, the idyllic Bakunin family estate 150 miles outside of Moscow that is tended to by 500 “souls” or serfs, and ends, many shifts in locale later, in 1868, at a rented château in Switzerland — and introduces more than 70 characters in all: the six male principals, various womenfolk (the female cast includes Amy Irving, Jennifer Ehle and Martha Plimpton), children, nannies and servants. The trilogy revolves around a group of influential Russian figures who meet as students in Moscow during the late 1820s. Czar Nicholas had brutally suppressed the Decembrist revolt of 1825, and the group — which, in addition to Bakunin and Belinsky, includes the political theorist and memoirist Alexander Herzen (Brian F. O’Byrne), the novelist Ivan Turgenev (Jason Butler Harner), the philosopher Nicholas Stankevich (David Barbour) and the poet Nicholas Ogarev (Josh Hamilton) — is jointly inspired by the romantic revolutionary ideals that linger in the air. “Voyage,” which runs for almost three hours, cuts back and forth between the insulated world of Premukhino, where the four singularly well-educated Bakunin sisters eagerly await the latest cultural news from their adored brother Mikhail, and the stimulating world of Moscow itself, where skating parties and Old World soirees with their liveried servants coexist with the new energy that fuels The Telescope, the small literary magazine in which Belinsky and his friends publish their incendiary views.

Like all Stoppard endeavors, “Voyage” is chunky with cerebration, enamored of ideas more than of people, and designed to entertain, educate and intimidate theater audiences all at the same time. Beneath the hum of concentration — we are now in the fourth scene of the second act, set in The Telescope’s drab offices in the summer of 1835 — Stoppard leans over and speaks in a quiet voice that has about it an air of declarative finesse, a projection of polite authority. He enunciates his words in a crisp, plummy British accent (pronouncing “issue” as “ISS-yew”) that bears scant trace of his émigré status — Stoppard, who was born Tomas Straussler on July 3, 1937, in Czechoslovakia, escaped the Nazis with his family and landed in England when he was 8 — except for the Mitteleuropean roll he gives his r’s. “The last time I was in a technical,” he says, “was at the Royal Court Theater — and you can imagine how different that was.” I nod as if I can imagine it, although I can’t, but there is something about Stoppard that inspires the wish to prove worthy of him. (“I think most people working with Tom would like to feel they were speaking his language, and if not intellectual equals, somewhere in the same neighborhood,” O’Brien said. “Few of us are, but we all continually seek his approval.”)

Stoppard leans over again a minute or so later and whispers, “I love scrims.” He is referring to the sheer cotton or linen hangings that are used as opaque backdrops or semitransparent curtains. This strikes me as a comment straight out of Wilde, much like his character Guildenstern’s line “Give us this day our daily mask,” suggesting a preference for the veiled over the overt, for artifice over reality. Stoppard says it with a measure of catch-me-if-you-can irony. Do not come any closer. Full stop. Trespassers will be made to feel foolish, or worse yet, presumptuous. Full stop. Or maybe I read all this sub-rosa meaning into what is in the end is just a clever comment only after the fact, once I have met with the playwright several more times and still find myself scrambling for clues to the man behind the poise.

Around an hour into the rehearsal, Stoppard and I repair to a small table in the corner of the theater lobby for conversation and a much needed smoking break for him. Stoppard, who is 69, is frequently photographed with a cigarette hanging off the end of his lower lip, like an Aging but Perpetually Angry Young Man, although he was hardly ever that — not even before “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” brought him international prominence nearly 40 years ago. “Very seldom has a play by a new dramatist been hailed with such rapturous unanimity,” Kenneth Tynan observed in his 1977 profile of Stoppard in The New Yorker. Right from the start, while he was still working as an underpaid journalist and writing his one and only novel, “Lord Malquist & Mr. Moon” (which was published to little stir in 1966, a year before the triumph of “Rosencrantz”), Stoppard appears to have had the habits of a squire rather than those of a subversive. According to his long-time agent, Kenneth Ewing, his client was always inclined to luxury. “When I first met Tom,” Ewing is quoted in Tynan’s profile, “he had just given up his regular work as a journalist in Bristol, and he was broke. But I noticed that even then he always traveled by taxi, never by bus. It was as if he knew that his time would come.”

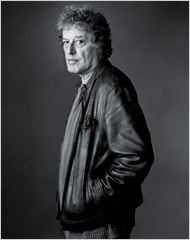

Stoppard cajoles an accommodating guard into overlooking his cigarette interlude; he smokes Silk Cut but will settle for Dunhill when he can’t find any. Before he lights up, he holds out a roll of candy and offers me what he describes as “a sophisticated Life Saver,” piquing my curiosity; and even when it turns out to be the ordinary article, I’m all the same convinced my red Life Saver tastes more exceptional because of his introduction. Stoppard would be a striking presence in any setting, with his glamorous half-rocker, half-brainiac looks: the poetically shadowed dark eyes, voluptuously puffy mouth, pre-Raphaelite head of tousled graying hair and elegantly insouciant style of dressing, which all three times I meet him feature as its centerpiece a chicly weathered (but brand-new) leather jacket that looks like something out of a John Varvatos ad and one or the other natty pair of shoes — today’s are a Tod’s white canvas number, and on another occasion he wears a pair of elegant leather sneakers by Zegna. (Although Stoppard chooses to ignore most of my painstakingly composed e-mail inquiries, he is willing to provide the provenance of his wardrobe.) Tina Brown, who met the writer when she was a 16-year-old living not far from him in Buckinghamshire, describes Stoppard as “an 18th-century figure, in his flourish and his mystery.” She adds that the first thing she noticed about him were his shoes.

I look at him and am struck by the aura of louche glamour he carries — like a lounge lizard who reads Flaubert — daring you to cause ripples in his carefully arranged and well-defended image. It is a daunting presentation — Stoppard referred to his “unfortunate and relentless facetious streak” in a talk with the theater critic John Lahr that I went to the day before — and I begin to understand, even before I try to draw him out, why everything I have read about Stoppard seems to recycle the same anecdotes and quips. (He tells me, for instance, that he writes poetry, but “only for domestic consumption,” a line that I appreciate a bit less after I come across it in an interview he gave more than a decade earlier.) The critic Clive James has called Stoppard a “dream interview, talking in eerily quotable sentences.” But it strikes me that it is precisely the acrobatically clever quality of those sentences that keeps real scrutiny at bay. Although there seems something genuinely shy about him under his debonair manner (“It takes a lot of effort to be vibrant,” he told me, almost as an aside, the first time we met. “Sometimes after the door closes, I feel my face fall”), there is also a weary hauteur of renown that hovers around the edges of his courtesy, leading him to make high-strung, Greta Garbo-ish statements. “I don’t do interviews under false pretenses,” he told me the following week. “My aim will be to be as boring as possible. I flinch when I see my name in the newspapers.” Then again, he is not unaware of how complicated his whole dance with the press is: “My reticence,” he states, “is a form of conceit, not of modesty. It has to do with not making myself available.”

Stoppard leans back — he has the kind of gangly physique that makes it look as if he’s loping along even when he’s just sitting in a chair — and explains that the process of writing the play is a “self-sufficient” one, which suits him (“I’m antisocial, really”), but that the trouble begins once the words are out of his hands. “Then it turns into something terrifying, a discussion of candles and matches.”

The truth of the matter is that Stoppard is deeply involved in facilitating the transfer of his scripts to the stage. In a 1995 interview with the New York Times drama critic Mel Gussow, he described his approach: “It’s the equivalent of the potter and the clay. I just love getting my hands in it. Clearly there are many writers who can mail the play in. . . . It stays the way they write it, I am told. I think they miss all the fun. I change things to accommodate something in the scenery, or something in the lighting. Happily.

I love being part of the equation. I don’t want it to be what happens to my text. I like the text to be part of the clay which is being molded.”

Carey Perloff, the artistic director of the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, has put on eight of Stoppard’s plays over the last 15 years and says the interest Stoppard takes in the production is unusual. “He has an enormous generosity of spirit as a collaborator in the room,” Perloff observes. “He’s the one playwright I know who buys presents for every single member of the crew. He remembers the people who make his plays work and also remembers their names.” When I took a walk with Stoppard in SoHo one afternoon, helping him look for a hostess gift — he finally decided on a pair of fashionable but not stridently trendy earrings, after inquiring whether I thought most women have pierced ears — he informed me, with a kind of shy pride, that he had gone into Barnes & Noble the night before and bought up all the Russian novels they had in stock to give as presents to the actors. “I had to double up on some. They were alphabetized, so I just went down the list: Chekov, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev.”

The fact that Stoppard continues to tinker with his plays — to revise and rethink them — after they’ve been written is a virtue in Perloff’s eyes. “Theater is an experiential art form,” she quotes him as saying. “If it doesn’t work, we’ll change it.” O’Brien, who is as versatile a director as Stoppard is a writer (he won a Tony in 2004 for Lincoln Center’s production of “Henry IV” after winning a Tony the year before for the musical “Hairspray”), has had ample opportunity to test Stoppard’s receptivity to making changes, especially since the director has a very specific idea of his own mission in staging Stoppard’s work. “I can get the sex in there,” he explains. “That’s what I think my job is. I’ve got to find the blood and heart because he has head enough for 50.”

O’Brien recalls that when he began to make recommendations for the script (“I frankly started cutting the stuff I didn’t think would sell”), Stoppard took some suggestions and fiercely resisted others. “He wrote back, ‘No, no, no,’ ” O’Brien says, “and I’d say back, ‘Yes but no.’ ” Stoppard’s account — as expressed in a postscript to one of his e-mail messages — is slightly different in its emphasis: “Jack didn’t ‘cut the play,’ ” he wrote. “He suggested some trims which I accepted when they coincided with my own and rejected when they didn’t.” In a message immediately following, Stoppard referred to this postscript and proceeded to clarify his point further — which, given his generally unexpansive style, is an indication of how important the subject of dramatic collaboration is to him. “You have to distinguish between text and production,” he wrote. “In the case of the latter, the director doesn’t have ‘input’ — the whole conception is his (working with a designer), and it’s the author who may or may not have some input. In the case of ‘Utopia,’ my input is marginal. I and the text are the beneficiaries. In the case of the text, in theater (unlike the movies) the writer is the final arbiter.”

Stoppard has written for film as well as television (his screenwriting credits include “Brazil,” “Empire of the Sun” and “Shakespeare in Love,” for which he won an Oscar), but his commitment to theater is very real. When I asked him why he chose it as his medium — and why he stuck with it — he responded via e-mail: “The standing of the theater in 1960 did have a lot to do with it. But it’s not just that. I like the smell of it, and the immediacy. Also the danger: getting it wrong in public. Also the thrill when you get it right in public.”

As has been the case with many of his other plays, “The Coast of Utopia” was inspired by Stoppard’s avid reading in a field that intrigued him. His interest can be sparked by an overheard remark, a newspaper article or a biography he’s read of Byron. “My life,” he once remarked, “is sectioned off into hot flushes, pursuits of this or that.” In his acknowledgment to the texts of “Utopia,” Stoppard cites Isaiah Berlin’s “Russian Thinkers” as well as E. H. Carr’s “Romantic Exiles” as his primary influences. (“Travesties” drew on Richard Ellmann’s biography of James Joyce, “Hapgood” on Richard Feynman’s writing on quantum physics and “Arcadia” on James Gleick’s book about chaos theory.) Stoppard — whose concerns resemble those of an Oxbridge don more than those of someone who chose not to attend university in order to pursue journalism — has always approached the intellectual backdrop of his plays with the zeal of an autodidact, sedulously researching historical facts and biographical accounts.

Indeed, it might be said that there is an aspect of high bluffing in Stoppard’s work, as if a gifted graduate student had suddenly decided to cram for an end-of-term exam on the origins of German romanticism without knowing a word of German. (Though he has regularly been compared with the multilingual Vladimir Nabokov for his polished use of words, and though he likes to drop foreign phrases in his plays — “Utopia” trots out full sentences in German, Russian, French and Italian — Stoppard’s languages are, by his own account, English and “bad French.”) Although he cheerfully insists that he reads only one out of every 10 books he buys — “I’m going to be dead before I read the books I’m going to read” — and that he should schedule an appointment for reading into his diary so that he doesn’t just “putter about tidying up my desk and making phone calls,” Stoppard is in fact in the midst of reading two books when we meet. One is a history of Prussia though 1947 (“I got as far as the 17th century”), and the other is a book by Adam Sisman on the friendship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, which he recommends highly. Thinking I am doing him a service in kind, I recommend a recent book about Turgenev only to discover that his reading, like so much about Stoppard, is of an expeditious rather than random nature — I’ve misconstrued his playful turn of mind for a kind of meandering, purposeless curiosity about people and ideas. “I’m done with Turgenev,” he says with so much finality that I find myself feeling sorry for poor dismissed Turgenev, no more grist in that mill.

Stoppard strikes me as an inveterately bookish man, one more passionately taken up with the life of the mind than with his aversion to being mistaken for a Serious Issues kind of playwright would indicate. Many years ago, in an article in The Sunday Times of London, Stoppard noted: “Some writers write because they burn with a cause which they further by writing about it. I burn with no causes. I cannot say that I write with any social objective. One writes because one loves writing, really.” In the almost 40 years since he made this remark, Stoppard has moved toward exhibiting a greater show of ideological esprit de corps — he took up the cudgels on behalf of Vaclav Havel when he was imprisoned in the late 70s and wrote a play during the same period that explored the psychiatric abuse of political dissidents in the Soviet Union, “Every Good Boy Deserves Favor” — but he continues to remain relatively aloof from the fray. Among other things, he has made no bones about his conservative temperament (when Margaret Thatcher came to power, he was one of the few among Britain’s left-leaning intelligentsia to see light at the end of the tunnel), which has led some observers to dismiss him as elitist. What is clear is that unlike, say, David Hare or the latter-day Harold Pinter, Stoppard is unwilling to hand down moral pronouncements by way of his plays about the absolute rightness or wrongness of one position or cause over another.

Perhaps this helps to explain Stoppard’s curious and somewhat leery attitude toward the discovery of his own tragic origins. As the son of a Czech Jewish mother who spent nine itinerant years during the late ’30s and ’40s fleeing Hitler’s net and finally found a haven in England, courtesy of her second husband, a British army officer whom she met and married in India in 1945, Stoppard must have learned the art of camouflage early on. (Dr. Eugen Straussler, the father of Tom and his older brother, disappeared during his family’s movements.) Although Kenneth Stoppard acted as a father to his new wife’s two young boys (the couple eventually had two children of their own) and endowed them with his impregnably British name, his patriarchal gestures came at a price. He held his sons to strict standards of behavior, and his xenophobia included an anti-Semitic streak. In a revealing yet detached essay Stoppard wrote in 1999 for the premiere issue of Talk magazine, “On Turning Out to Be Jewish,” he revealed that his mother draped a cautionary veil of silence about the particulars of their own background and that he was made to feel obliged to his stepfather for providing him with the immunity of his transplanted citizenship: “Don’t you realize that I made you British?” Stoppard recounts his stepfather reprimanding him when he once, in his 9-year-old innocence, mentioned his “real father.” According to this article, it was only in his mid-50s that Stoppard learned that both sets of his grandparents — in addition to a handful of aunts and uncles — were killed in concentration camps, as well as the final destiny of his father, who died in an attempt to escape from Singapore when the boat he was on was sunk by Japanese bombers. Stoppard also discloses, in his understated way (“I’ve been very used to making a drama out of as little as possible,” he told me) that when his stepfather, shortly after Stoppard’s mother died in 1996, wanted to retrieve his last name in a fit of pique with Stoppard’s growing “tribalization” (“by which he meant,” Stoppard writes, “mainly my association 10 years earlier with the cause of Russian Jews”), his stepson chose to ignore the request: “I wrote back that this was not practical.”

You sense that for Stoppard there is real peril in looking back — even perhaps in the very attitude of nostalgia — and that he feels compelled to forget in order to go on. “I take refuge,” he told John Lahr, “in the fact that I can’t change anything by agonizing about it, so I don’t.” A little later in that same conversation he said, “When you let your subconscious off the leash, it leads you other places.” When I asked Stoppard why he hadn’t been more curious about his background when he was growing up or when his mother was still alive to provide some answers, he replied, “I became somebody who didn’t ask.”

At noon a few days after the tech rehearsal, I met Stoppard for lunch at O’Neal’s, a restaurant near Lincoln Center. To be precise, we arranged to meet not actually at O’Neal’s but at the magazine store a block away where Stoppard goes to pick up the British dailies The Guardian and The Telegraph. From there we wandered into the restaurant, which was all but empty at this hour, and settled into a corner table. Stoppard had been living in New York in a sublet near Lincoln Center since the beginning of September and plans to stay through the middle of February, overseeing the successive rehearsals of all three parts of “Utopia,” with periodic absences. He flew to Moscow for a week at the end of September to look in on a Russian production of “Utopia” that is planned for April, and he has been going back and forth to England to check in on “Rock ’n’ Roll,” his latest play, among other things. (Stoppard, who is divorced, has four sons living there and is expecting his seventh grandchild in January.) He said he felt at home in his temporary digs but that the one thing he had taken exception to was sleeping on borrowed sheets, so he went out and acquired some new ones. Stoppard claimed to have been dismayed by the prices: “I had no idea,” he said, “that sheets cost the same as a small BMW.”

The line is funny, but I find it hard to believe that a man who is used to living on Stoppard’s baronial level doesn’t know the prices of luxury goods. He hobnobs with Mick Jagger, has been invited to taste wine from Baron Philippe de Rothschild’s private cellars and before he was divorced from his second wife, Miriam — a physician who is a well-known health-book writer and TV personality in England — in 1992, his home was a 17-acre country estate called Iver Grove. The property, an architecturally renowned Palladian mansion in the picturesquely named hamlet of Shredding Green, was used as a Polish refugee camp during World War II. During the Stoppards’ era, the Victorian brick stable was converted and renovated to include offices, an in-law suite and a glass-enclosed billiard room.

Then too, Stoppard seems to be a man of discerning and somewhat rarefied tastes; he writes with a fountain pen (no Uniballs for him) and has a house in the French countryside to retreat to when he’s not in London. In the memoir “Untold Stories,” the playwright Alan Bennett used his rival as a metaphor for all that is shimmeringly patrician and out of reach: “At the drabber moments of my life (swilling some excrement from the steps, for instance, or rooting with a bent coat hanger down a blocked sink), thoughts occur like, I bet Tom Stoppard doesn’t have to do this.”

Stoppard and I both ordered coffee, and as a waitress hovered anxiously, he told me he had agreed to write a foreword to a reissue of Kenneth Tynan’s diaries (Tynan, one of Stoppard’s earliest supporters, was responsible for bringing “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” to Laurence Olivier’s attention at the National Theater) and had turned down an invitation to do the Proust Questionnaire in Vanity Fair. There was an audible flicker of disdain in his voice as he mimicked the impertinent nosiness of the questions he would have been expected to answer: “What do you hate about yourself? What do you like most?” I decided to take the bull by the horns: “Would you know,” I asked, “what you hate about yourself?” Stoppard paused, looking hard at me. “Well, yes,” he said, sounding slightly put off. “I could come up with something after a few minutes.” At my further prodding, we discussed Stoppard’s resistance to self-examination, which Carey Perloff attributes to his “English side” and which I find nonetheless puzzling in a man who enjoys the act of reflection as much as he does. “I’m a little suspicious,” he said, “of my own antipathy to going to a shrink. Perhaps it means I need to go to one.” He was indulging me, of course; I don’t believe he has given more than a moment’s thought to therapy and its vicissitudes, which suspicion was immediately confirmed by his next sentence: “My disinclination to analyze myself suggests I wouldn’t pay someone else to do it.”

The longer I ponder the Stoppard legend — the difficult beginnings and then the smooth ascent, with nary a glitch to be seen — the more I find myself wondering at the gaps in his history, at how much he has discarded along the road. “We had a new life, and we weren’t going to bring our baggage with us,” he told John Lahr, when pressed to give an account of how he dealt with the elisions of his childhood. In one of our meetings, Stoppard posed the quandary: “One of the questions that haunts me — it’s a question for philosophers and brain science — is, if you’ve forgotten a book, is that the same as never having read it?” With just a slight twist, you could put the question another way and it would contain all the intrigue and wily psychic machinations that have accompanied Stoppard throughout his blazing achievements and rich personal life: if you forget the unpleasant experiences you’ve once lived through — if you choose to begin the tape at 1946 instead of 1937 — does that mean they never happened? Stoppard may in fact be that rare creature, an untortured creative artist for whom art is not an escape from trauma but rather an extension of his intellectual largess. Or he may be someone stuck in his own characterization, playing out the upside of an absurdist existential situation — like the bewildered summation he put in the mouth of Ogarev, the cuckolded poet in “Utopia,” who ends up in a West End slum speaking broken English, a former aristocrat reduced to drunken dependency on his younger, crass mistress: “It’s just like life — waking up in your own bed and not knowing how you got there.”

The fact that the downside is increasingly present in Stoppard’s vision suggests that he is more willing than he has been to confront the historical landscape of loss and uprootedness. “The Coast of Utopia” takes in the plight of exile — “the flotsam of refugees forever going over the past,” as Alexander Herzen, the trilogy’s presiding presence describes them — with a sharp but sympathetic eye. If you’re not too busy being amused by Stoppard’s epigrammatic deftness throughout “Utopia,” his uncanny ability to bring together discordant parts into a resoundingly satisfying whole, you might notice that what links everything and everyone is a feeling of untold loss and undwelled-on heartache, infusing all the bright chatter and energetic stomping in and out of romance and revolution with an atmosphere of Chekovian twilight, a quality of withheld sadness.

Daphne Merkin is a contributing writer for the magazine.